Going with the flow: Hydropower projects gain momentum

By EPR Magazine Editorial April 28, 2020 12:21 pm IST

By EPR Magazine Editorial April 28, 2020 12:21 pm IST

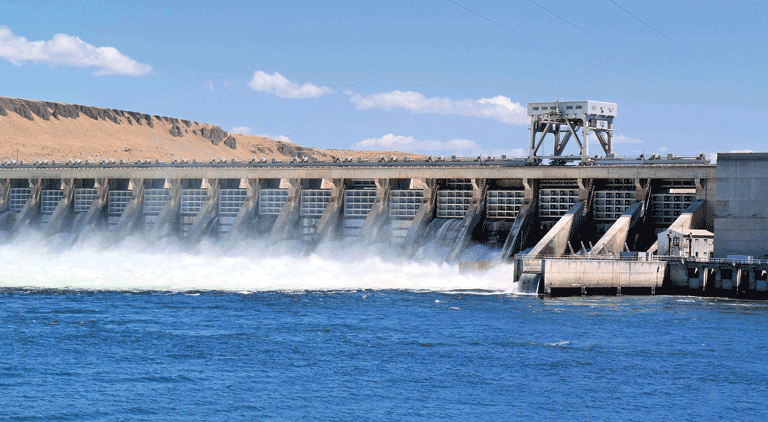

With large-sized hydro projects expected to emerge in the next few years and a slew of recent policy amendments by the government, hydropower seems poised for growth in India, more so as even during the ongoing COVID-19 national lockdown, numerous tenders have been floated by various government utilities for greenfield and rehabilitation projects.

Hydropower as a source of clean and green power is well-known globally. In India, with an installed base of approximately 50.1 GW, and another 4.67 GW from small hydropower (SHP), it is well-poised to grow further. India’s ambitious renewable energy (RE) capacity addition of 175 GW by 2022 is more or less on track, and with a behemoth of RE capacity addition through grid connectivity, hydropower would be required as a way to maintain grid stability in the coming years. In 2019, the government of India covered all hydropower projects under renewable energy category to provide more impetus to the RE sector.

What was witnessed in the last 4-5 years was a complete sluggishness in hydropower. The main reasons were geological surprises in ongoing projects, leading to inordinate delays and project cost overruns. This was coupled with lack of fresh financing coming into the sector and hence, certain projects were nearly declared as NPAs and creditors filed for recovery through the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT).

As on 29th February 2020, about 11 stressed hydro assets have seen some revival steps, including bidding through NCLT. While there was no fresh equity infusion in existing hydro projects as lenders stopped taking further exposure, projects with long overruns did not see any hope for revival. However, the government has made some amendments recently in 2019 to the existing hydropower policy through amendment. Namely four major issues were addressed, including Hydro Purchase Obligation limited to specific conditions, categorisation of all hydro projects under RE, rationalising of hydro energy tariff (incentives and tax rebates), and budgetary support for cost of enabling infrastructure and flood moderation components. These amendments will definitely assist the revival of the sector.

Hopefully, the worst is behind us now and we could probably see movements in large-sized hydro projects in Arunachal Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir. There is movement also seen in hydro pumped-storage plants (PSPs), which are one of the best suited energy storage plants to mitigate grid instability coming from erratic power sources such as solar and wind power.

India’s small hydro potential is 21,133 MW, of which only 4,683 MW has been installed until 31st March 2020. Considerable growth is expected in this domain with the formation of Renewable Energy Corporation in J&K and Himachal Pradesh, who have introduced changes in policy to attract developers with better co-ordination between MNRE and State Nodal agencies. We also expect projects in North Eastern states to be given due attention owing to geopolitical reasons.

The total small hydro project sites identified are 1,001 in number that aggregate to a capacity of 3,832 MW. From this, 1,662 MW from 320 projects is being generated by independent power producers (IPPs). In India, the small hydropower plants are mainly run-off-the-river type and they have advantages that in the construction of these small ROR type projects, there are no issues of deforestation, resettlement and rehabilitation, which otherwise aremajor issues in hydro project implementation.With the recent development in Jammu & Kashmir regarding the scrapping of Article 370, the government of India is looking at speeding up strategically important hydropower projects in the state. These hydro projects located mainly in the Chenab Valley will be developed expeditiously due to geopolitical issues bearing out of the existing Indus Water Treaty between India and Pakistan. Further, China’s OBOR has propelled the government to move on priority on implementing large projects like Ratle, Sawalkote, Pakal Dul, Kwar, and Kiru. Of these projects, Pakal Dul and Kiru have already been awarded for civil, hydromechanical and electromechanical works.

India’s largest state-owned hydropower utility, namely NHPC, floated the tender for civil and hydromechanical works in April 2020 for the prestigious Dibang hydropower project (2,880 MW) located in Arunachal Pradesh. These are encouraging movements in the Indian hydropower sector. In the southern states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, we expect life extension initiatives of various aged hydro plants that have an average life of 55 years and are in dire need of renovation and modernisation.

With the increase in RE capacity addition, we expect to see movement on hydro pumped-storage schemes (PSPs). Namely projects like Turga PSP (1,000 MW), Bandha Nala (900 MW), Lugu Pahar PSP (1,500 MW) and a few more large-sized projects are expected to come up in the next 1-3 years. Further, as a first-time step, an IPP based in Hyderabad has started contracting works for one of the largest PSPs, namely the Pinnapuram multi-purpose project in India.

Teesta-VI (500 MW) in Sikkim, which was previously being developed by an IPP, was finally reprieved through NCLT, and NHPC will take over the project. The much-needed funding seems to be one of the many impediments being faced in the hydropower sector at the moment. With the recent amendments to the hydro policy, we might just have to wait till backlogs clear up and we see a slew of projects coming up for development this year.

We use cookies to personalize your experience. By continuing to visit this website you agree to our Terms & Conditions, Privacy Policy and Cookie Policy.